The Simple (1st class) Lever (animation)

Key Terms

eccentric pulley

mechanical advantage

lever

lever arm

power

torque

wheel and axle

"Give me a place to stand and I will move the earth" ... Archimedes

Since humans have limited strength, clever people have built machines that allow feats not previously possible. One of the simplest (and most likely the first) machine is the lever. I'm sure you discovered the magic of the lever as a youngster when you played on the teeter-totter. Somehow, little sister is able to counter the weight of big brother by careful positioning on the apparatus. This may seem very intuitive, but still, it is a device that needed to be invented. Applications of the lever can be found all around your household.

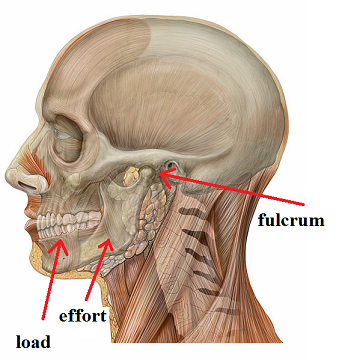

A lever consists of a rigid bar that is able to pivot at one point. This point of rotation is known as the fulcrum. A force is applied at some point away from the fulcrum (typically called the effort). This force initiates a tendency to rotate the bar about the fulcrum. The idea is to provide another force to lift or move some object (typically called the load). Consider the animation below. In order to lift the weight on the left (the load) a downward effort force is required on the right side of the lever. Common sense tells you that the amount of effort force required to raise the load depends on where the force is applied. I'm sure you are aware that the task will be easiest if the effort force is applied as far from the fulcrum as possible.

The Simple (1st class) Lever (animation)

Let's say the load (above) is 200 pounds and you need to lift it 1 foot off the ground. This would require 200 * 1 = 200 foot-pounds of work (in the absence of friction). By using a lever, you can lift it with a much smaller force ... depending on where the effort force is applied. The fact that you can lift something heavy with a small force is the key to any simple machine. Most simple machines (like the lever) provides you with a mechanical advantage (a force multiplier = load force/effort force). However, do not think for a second that a simple machine is somehow violating the laws of energy conservation. The amount of energy you get out is exactly equal to the energy you put in. That is, since energy can not be created or destroyed, you will always find:

Energy (out) = Energy (in)

To simplify things we will not consider the weight of the bar itself and only consider frictionless situations (no losses that result in heat). This way

Work (out) = Work (in)

LOAD FORCE * distance (upward) = effort force * DISTANCE (downward)

200 lbs * 1 foot = 25 lbs * 8 feet

or

200 lbs * 1 foot = 100 lbs * 2 feet

The key, therefore, is to trade force for distance. You can lift the 200 pound load a short distance (1 foot upward) by exerting a smaller force over a larger distance. However, no matter where you apply the effort force it will take 200 foot-pounds of work.

Consider the example where you are lifting a 200 pound load upward 1 foot (in the example above). Try to answer the following questions. Click here to see the answers.

Question #1 - Using your own words; explain where the effort must be applied to insure that the effort force is exactly 200 pounds.

Question #2 - In this instance, what is the mechanical advantage?

Question #3 - Using your own words; explain where the effort must be applied to insure that the effort force is less than 200 pounds.

Question #4 - If you exert an effort force of 50 pounds, through what (vertical) distance is it applied?

Levers are classified as 1st, 2nd and 3rd class. The images below demonstrate each type with the effort force shown as an arrow and the load represented by a black sphere.

Old time bottle opener and traditional nutcracker (animation)

Adapted from Wikimedia Commons

Can you think of several examples of each class of lever?

Question #6 - To which class of lever would you classify (a) pliers (b) hand brakes on a bike (c) tweezers (d) hockey stick (e) car door ... the load being the mass of the door (f) mouse trap

It should now be obvious that the distance the effort (and load) is from the fulcrum becomes an important factor related to the lever. The farther the effort force is applied from the pivot, the easier it is to produce rotation. These factors are incorporated in a term called torque. You probably already had a feeling that torque dealt with the turning effect of a force.

Two ways to achieve the same torque (animation)

Anyone who has ever tried to loosen a rusty nut with a wrench knows about torque. The animation above shows two ways to accomplish the goal ... exert a big force close to the rusty nut or apply a smaller force farther from the axis of rotation. How many of you have added a piece of pipe to the end of your wrench to persuade it to move? In fact, many nuts need to be tightened to very specific specifications. This is when you use a torque wrench (a special tool designed to deliver just the right amount of tightening).

A torque wrench will tighten a bolt with just the right amount of "twist".

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Torque and work are two different things. Consider a force applied perpendicular to a metal bar (as seen in the image below):

|

|

Torque = Applied Force * Lever Arm Work = Force * Distance

If the lever arm is 8 feet and the applied force is 10 pounds, the resulting torque is 80 foot-pounds (regardless if the system rotates). The actual work done in this example is equal to the force times the physical distance it moves (shown as a displacement of 1 foot). If the bar doesn't move at all, no work is done, but you still have 80 ft-lbs of torque in the system. That is, the work done and the torque produced are different quantities ... but measured in the same units. You can think of torque as the "twisting effects" of a force and work as the energy used in moving something.

When considering the (frictionless) lever:

Work (out) = Work (in)

Torque (out) = Torque (in)

(animation)

Analysis from the standpoint of work

The concept of any simple machine is to accomplish a task by applying a smaller force over a greater distance. Consider the example shown below. Suppose you have to lift a 60 pound object a vertical distance of 1 foot. This requires 60 foot-pounds of work. You may not be capable of lifting 60 pounds (or get a sore back trying). However, a lever lets you lift the object with a much smaller force. Consider the drawing below where the 60 pound load is lifted a vertical distance of 1 foot (shown in pink next to the load). To lift the weight, you could apply a force of 12 pounds over a distance of 5 feet to lift the object ... or a force of 15 pounds over a distance of 4 feet ... etc. This gives you a mechanical advantage because you are exerting a force less than 60 pounds.. It is calculated as the ratio of the output force to the input force. If it takes 12 pounds to lift a 60 pound load, the mechanical advantage is 5 (60/12 = 5) ... if it takes 15 pounds to lift a 60 pound load, the mechanical advantage is 4. In all cases, you are doing the same amount of work. In the image below a force of 10 pounds must be exerted over a distance of 6 feet to produce 60 foot-pounds of work.

Lever animation in which the MA = 6

Note: We have analyzed the situation assuming no losses to friction. In the real world, the mechanical advantage calculated this way may be slightly lower because the effort force will be slightly higher than the ideal case.

Analysis from the standpoint of torque

Lever animation

Now let's analyze the same lever from the standpoint of torque. Assume the distance between (red) dots along the lever represents 2 feet. The 60 pound load rests 2 feet from the fulcrum, producing a counter-clockwise torque of 120 foot - pounds around the pivot point. A 10 pound force exerted 12 feet from the fulcrum will produce the same amount of clockwise torque ... enough to produce rotation. The ratio of input lever arm to the output lever arm will yield the mechanical advantage of 12/2 = 6. Thus, it is possible to estimate the mechanical advantage from direct observation. If the input lever arm is 6 times the length of the output lever arm, the system gives a mechanical advantage of 6, meaning that for every pound you push on the lever, you can lift 6 pounds of load.

A longer input lever arm (location of the effort) gives a higher mechanical advantage. This is consistent with the common sense idea that you usually apply the effort force as far from the fulcrum as possible.

Use this picture to answer these questions (answers are below)

Question #7 - Suppose this first class lever is used to lift a 100 pound object (load) by applying a downward effort force at point B. What is the mechanical advantage? What force is required?

Question #8 - If the effort force is applied at point A and the load moves 1 foot upward, how many feet must point A move down? How much work is done lifting this weight?

When pedaling a bike, you can not deliver a constant torque to the pedals. Torque is not only the product of the applied force times the lever arm ... it also depends on the direction the force is applied.

When you pedal a bike, there are parts of the "pedaling cycle" where you are doing nothing to provide power to the wheels because you are producing no torque to the pedals.. As a result, the power you provide to the wheels actually looks like a half sine wave no matter how hard you may be pushing on the pedals (unless you have those "clip on" devices that racers use which harness the foot to the pedal). You will find the same effect in an engine and electric motor.

Have you ever used a winch to move a boat up a trailer? ... or pull a bucket of water up a deep well? ... or snag that prize winning musky with your rod & reel? If you have, you were using a simple machine known as a wheel and axle. The wheel and axle is just another form of a simple lever. Can you see why? To which class of lever does it belong?

The Wheel and Axle is just a lever in disguise

Note: The "wheel and axle" should not be confused with the kind you find on a wagon ... which is just a wheel attached to an axle. The wheel (the one you roll) is just a device designed to reduce friction. The "wheel and axle" is something you turn to gain a mechanical advantage. A common winch (see image below) is an example of a "wheel and axle". Using only one person, you can draw a boat snug to the top of the trailer with this device (and you also have wheels which the boat rides on during this process to reduce friction).

Here are some examples of the "wheel and axle" I found around my home:

You should be able to come up with many other common examples of a "wheel and axle".

Single Pulleys

A single pulley gives you no mechanical advantage (actually the MA = 1) ... but it lets you lift a heavy object easily with the use of a counter-weight. If the counter-weight matches the load ... all you have to do is overcome friction, making the lift easy. Most elevators have a counter-weight which is equal to the weight of the elevator plus 40% of its maximum load.

A special kind of pulley, called an eccentric pulley, does give you a mechanical advantage because the center of rotation is not at the geometric center of the pulley. This can be found on a compound bow. If you have ever used a compound bow, you will find that initially, the bow is very difficult to pull back, but once pulled back far enough, it becomes quite easy to hold and steady. Why do we mention this kind of pulley here (in a section on levers)? This is because the eccentric pulley is a first class lever in disguise. At first, when you initially draw the arrow, you would normally expect the easiest effort, but it is actually quite difficult. The eccentric pulley produces a mechanical disadvantage in this position and you really have to strain at first. However, once you pull the arrow back (and expect the greatest struggle with the bow) ... it gets easy to hold and steady. This is because the pulley pivots around giving you a mechanical advantage.

The eccentric pulley is just a lever in disguise.

The Compound Bow - can you see that the eccentric pulley is really just a lever?

Power is nothing more than the rate at which work is done (how fast energy is being used). Common units are the watt and horsepower. The concept of power was covered in a previous unit, but needs our attention again because of how it is related to torque.

A car engine can only produce so much power. This power can be delivered to the wheels of the car in one of two ways ... torque and rpm (revolutions per minute). In fact, the formula looks like this:

Power (horsepower) = Torque (foot-pounds) * RPM ÷ 5252

This means that the power output of an engine must be managed to either produce a high torque at low speed or low torque at a high speed. This is where a car's transmission comes in. It is designed to deliver the proper torque and speed to the wheels using systems of gears.

It is much simpler to use an ordinary bicycle to illustrate the point. In this case, you are the device providing the output power to the wheels. The bike has a chain that transfers the power from the pedals to the back wheel. If there are no changeable gears on the bike ... it becomes very basic ... if you want to go faster ... you have to pedal harder (produce more power output). Also, you have to pedal harder if you start going up a hill (need more torque at the wheels). Gears let you exert yourself about the same, but allows you to trade speed for torque or vice versa. When the chain by the pedal is set on the smallest gear and the rear axle (wheel) is set on the largest gear, you are trading speed for torque. You will go very slow, but provide a high torque at the wheels (for going up a hill). When going down a hill, you need very little torque at the wheels so you reverse the gears and get lots of speed. The same thing happens with your car. The engine's power output can be fairly constant but the transmission plays the same torque vs. speed game as the gears on a bike. If you want to go up a steep hill, you need more torque at the wheels so you need to sacrifice speed (RPM's) to accomplish the task.

©2001, 2004, 2007, 2009, 2016 by Jim Mihal - All rights reserved

No portion may be distributed without the expressed written permission of the author

Question #1 - The effort force must be applied as far from fulcrum as the load is from the fulcrum. That is, symmetry rules, so the right side is a mirror image of the left side.

Question #2 - The MA is 1. No advantage, no disadvantage. The mechanical advantage is the ratio of the load/effort ... 200/200 = 1

Question #3 - The effort force must be applied farther from the fulcrum than the load is from the fulcrum.

Question #4 - 200 foot-pounds = x feet * 50 pounds x = 4 feet

Question #5 - In some cases you are more interested in freedom of motion rather than force multiplication. In this case, you provide a large effort force over a short distance to provide a smaller force over a larger distance. Many hydraulic systems need to apply this type of lever because the output piston doesn't move very far. Look carefully at some heavy construction equipment, snow plows and/or earth movers. You will likely see some 1st class levers where the hydraulics act as the effort force, but offer a wide range of output motion.

This animation shows 3 levers which all produce a mechanical disadvantage.

Question #6 - a. 1st class b. 2nd class c. 3rd class d. 3rd class (one hand is the fulcrum, the other is the effort) e. 2nd class (load can be considered the center of the door) f. 3rd class (effort provided by a spring close to the pivot)

Question #7 - MA = 2 by looking at the ratio of lever arms. Since the MA is 2, the force multiplier is 2. The required effort force is 50 pounds.

Question #8 - Work = 1 foot * 100 pounds = 100 foot pounds. Point A must move downward 3 feet. The MA =3 so the effort is 33 1/3 pounds. Since work in = work out, we need 100 ft-lbs of input energy. 33 1/3 pounds * 3 feet = 100 foot pounds of work.