Clouds, Rain, & Storms

Basically there are two main types of clouds:

cumulus = puffy clouds ... usually associated with fair weather.

stratus = vast cloud layer covering most or all of the sky.

Each cloud can be found at different heights ...

alto = middle height

cirro = high

nimbo = rain making

So a cirrostratus cloud is a very high stratus cloud. Other types include:

cirrus (thin, wispy and very high)

cumulonimbus (large

towering thunderhead clouds ... a sure sign that bad weather is near)

At the end of this page there are links to several images or click here for a cloud types link.

What is a cloud? When you are standing in fog, you are standing in a cloud (a very low one). The air in a cloud is at its dew point (100% relative humidity ... or saturated). Under this condition, it is very easy for water vapor to condense to liquid. In the air, it does so on any tiny particle "floating" in the air called a condensation nuclei (dust, smoke, salts, etc.). The actual water droplet in a cloud is quite small. It takes 1,000,000 of these "cloud droplets" to make one drop of water. So, to make a cloud, all you have to do is cool air to its dew point! For example, if the night sky is cloud free and the air at the surface is very still ... you will likely wake up to fog. Why? Because a clear night sky means lots of radiation can escape to space (cooling the air) and if the cool surface air doesn't thermally mix with layers above (still air) ... the dew point is reached ... making fog. In most all other cases, the air is cooled to its dew point because the air is rising ... expanding .... and cooling!

|

|

|

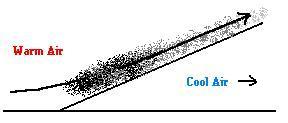

Warm Fronts - Suppose a warm front is approaching your area but the actual front (as seen on the weather map) is actually quite a distance away (even over 500 miles away). Even at that distance, the careful observer will notice changes in the sky warning him/her that the front is approaching.

(animation)

(animation)

The animation above attempts to show that as a warm front approaches, there are a series of changes a stationary observer will notice well before the front actually crosses the area. The observer at point "A" will start seeing the first sign in the form of a cloud type called cirrus. This is a very high, thin and "wispy" cloud which looks like a horse's tail (so it is sometimes referred to as Mare's Tails).

As the front approaches, the stationary observer find himself/herself at point "B" (relative to the front). Looking up, the observer notices a very high and thin cloud cover which covers the entire sky and is nearly transparent. This is an Cirrostratus Clouds. This cloud is so high, it is almost all ice crystals which act like tiny prisms ... which refract the light of the sun or moon, forming a halo.

A halo around the moon formed by ice crystals acting as a prism

Soon the observer is at point "C" looking up. He/she notices that the stratus cloud is getting lower and thicker. It is an altostratus cloud which makes the daytime sun appear like a full moon.

It starts raining when the observer is at position "D". This rain is a steady rain or drizzle that can last days (depending on the speed of the front). You never even see the sun now and the cloud level is quite low. These clouds are called nimbostratus.

The front actually passes the observer at point "E", and there is a sudden change in the weather. It gets warmer, sunny, winds shift from the south, and it's time to cut the grass.

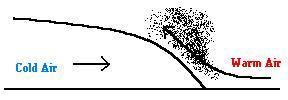

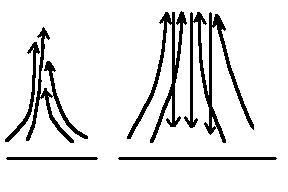

Cold Fronts - This front is associated with severe weather including hail and tornadoes. The swift and violent lifting of warm moist air releases lots of energy to the atmosphere in the form of latent heat. The appearance of huge, towering cumulonimbus clouds are a sure sign that bad weather is coming.

What is latent heat? Have you ever felt chilled when leaving a shower? Or experienced a "cooling sensation" when gasoline drips on your hand? This is not your imagination. As water evaporates off your skin, it absorbs a huge chunk of heat energy as well. This is why evaporating sweat promotes cooling. All this energy is then "hidden" in the vapor ... only to be released when the vapor condenses. During the violent uplift of warm moist air in a cold front, so much latent heat is released to the environment that it promotes even more uplift (remember ... warm air rises). This draws in more warm moist air toward the front and the cycle continues. It is like a bomb exploding in the atmosphere. Meteorologists say that the air is "unstable" when it has the capacity to behave this way. In this case, the "fuse" is the cold front which triggers the explosion. Maybe now you can see why the atmosphere can get so wild.

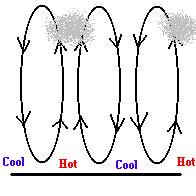

Air Mass Thunderstorms - Sometimes unstable air doesn't need a front to trigger the explosion ... it can do it all by itself. These "isolated" explosions are called Air Mass Thunderstorms or Supercell Thunderstorms (thunderstorms with deep rotating updrafts). You've all witnesses this type of thunderstorm. A beautiful summer day suddenly turns sour, and for a few hours you are scrambling for cover. Then, as quickly as it came, it is gone! What causes this? The typical conditions are: warm moist air at the surface and a steep temperature gradient vertically (it gets cold quickly as you move up in the atmosphere). This can cause the air to become unstable, and it only needs a "nudge" to get things going. The "nudge" could be one energetic updraft due to intense surface heating. If the updraft produces sufficient condensation and thus latent heat, the updraft is accelerated as the parcel of air heats itself, expands and becomes more buoyant. BOOM!

One last thing we need to discuss. How do you make rain? It almost sounds too simple, but the story puzzled meteorologists at first. If you recall, it takes over 1,000,000 cloud droplets to make one raindrop. The problem is, at such a small size, they tend to bounce off each other rather than stick together (due to the large surface tension at that size). So how do they get together? The answer is these "mini droplets" do stick to an ice crystal ... freezing to it making the crystal bigger. So just as you needed a condensation nuclei (dust, smoke, salts, etc.) to make the "mini droplet", you need a freezing nuclei to get the droplets together ... forming a snowflake. Essentially this means that (at least at our latitude), rain starts out as snow. This process is known as the Bergeron process. Once the flake gets large enough, it falls due to gravity. If it never gets warm enough to melt the flake ... get out the shovel. During warmer times, the flake will reach a height were it melts. At this larger size, the falling drop can collect more "mini droplets" in a process called collision coalescence. If the drop gets too big as it falls, it will break up into smaller falling drops and the process continues.

You can expect sever weather whenever air masses collide. Most books define an air mass as a large body of air with the same temperature and humidity. These masses may take a while to form, but once established, they may move from their place of origin and do battle with other air masses.

Air masses are categorized by two criteria.

If the air mass develops over land, it is called continental and

will start with a small "c". If it develops over water, called maritime

it will start with a small letter "m". Continental air masses are

obviously less humid than maritime air masses.

If the air mass develops in higher latitudes, it is called polar and ends with the capital letter "P". Air masses forming at lower latitudes are known as tropical and end with the capital letter "T".

Therefore, there are 4 main types of air masses: cT, cP, mT, and mP.

The US is too near the Polar Front to establish any well defined air mass of its own. Rather, it is the place where these masses migrate to and interact. Wisconsin is usually effected by 3 different air masses ... huge cP air blasts from Canada, and warm moist mT air from the Gulf of Mexico. On rare occasion, we can be influenced by a cT air mass coming from Mexico.

The most common natural hazards Wisconsinites need fear are tornadoes and lightning. Both are likely to occur during the clash of a Canadian cP air mass and a mT air mass moving out of the Gulf of Mexico. When this happens, the jet stream meanders wildly and strong mid-latitude cyclones (low pressure systems) develop. Dangerous weather appears along the associated warm fronts or cold fronts. The cold fronts are the most dangerous and frequent.

More people die annually from lightning than tornadoes and hurricanes put together (only floods claim more lives). It occurs when the electric charge built up in a cloud suddenly discharges to another cloud or the ground.

Lightning Safety Rules courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) U. S. Department of Commerce.

- Stay indoors, and don't venture outside, unless absolutely necessary.

- Stay away from open doors and windows, fireplaces, radiators, stoves, metal pipes, sinks, and plug-in electrical appliances.

- Don't use plug-in electrical equipment like hair driers, electric toothbrushes, or electric razors during the storm.

- Don't use the telephone during the storm. Lightning may strike telephone lines outside.

- Don't take laundry off the clothesline.

- Don't work on fences, telephone or power lines, pipelines, or structural steel fabrication.

- Don't use metal objects like fishing rods and golf clubs. Golfers wearing cleated shoes are particularly good lightning rods.

- Don't handle flammable materials in open containers.

- Stop tractor work, especially when the tractor is pulling metal equipment, and dismount. Tractors and other implements in metallic contact with the ground are often struck by lightning.

- Get out of the water and off small boats.

- Stay in your automobile if you are traveling. Automobiles offer excellent lightning protection. There are exceptions to this, however, as seen here.

- Seek shelter in buildings. If no buildings are available, your best protection is a cave, ditch, canyon, or under head-high clumps of trees in open forest glades.

- When there is no shelter, avoid the highest object in the area. If only isolated trees are nearby, your best protection is to crouch in the open, keeping twice as far away from isolated trees as the trees are high.

- Avoid hilltops, open spaces, wire fences, metal clotheslines, exposed sheds, and any electrically conductive elevated objects.

- When you feel the electrical charge -- if your hair stands on end or your skin tingles -- lightning may be about to strike you. Drop to the ground immediately.

Click here for some information and tips about lightning.

Click here to read when and where tornadoes occur.

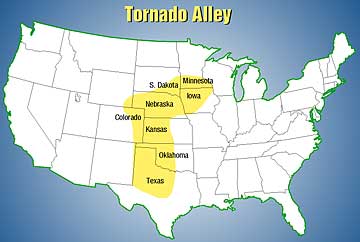

Although a tornado can occur in any month, the most likely time is May - June. The most likely place is a strip of land known as "tornado alley" (see diagram below). Tornadoes are most likely to occur between 3 p.m. and 9 p.m.

Both images from NOAA

Tornado Safety Rules courtesy of the National

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) U. S. Department of Commerce. Key Safety Rules

Click here for NOAA's tornado FAQ page

Click here for NOAA fast fact page on tornados

Click here for the NOAA tornado page

Here are some images of clouds by "soon to be" meteorologist or storm chaser, Mark Michels (a great former student of this class and his son, Alex)

altocumulus clouds 1

altocumulus clouds 2

altostratus stratus clouds

cirrocumulus

cirrostratus with halo

cirrus fibrous

precipitating cumulus

towering cumulus 1

towering cumulus 2

towering cumulus 3

ŠJim Mihal 2004 - all rights reserved